Proper biosecurity measures and an eye on feed can protect animals from existing and emerging disease challenges

Although there are always a variety of pathogens that threaten the health of swine in the U.S., recent years have been particularly challenging.

On top of known threats such as Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea virus (PEDv), Classical Swine Fever virus (CSFv or hog cholera) and Foot and Mouth Disease virus (FMDv), new risks are continually emerging. Recently pork producers faced a new, highly virulent strain of the Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRSv) — PRRSv 144 — that emerged in an unseasonable manner, leading to increased mortality and abortion rates. The threat of African Swine Fever virus (ASFv) for U.S. producers also lurks just around the corner, with confirmed cases in Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

These challenges remind us of the importance for producers to have comprehensive biosecurity plans in place to keep pathogens out, said Scott Dee, DVM, Director of Research for Pipestone Applied Research. Biosecurity protocols include everything from vaccinations to proper ventilation and air filtration systems, and shower in/shower out to truck washes.

A sometimes overlooked, but integral part of any biosecurity program is feed. Producers that don't have an eye on feed biosecurity run the risk of both domestic and foreign animal diseases being introduced and spreading through their herds.

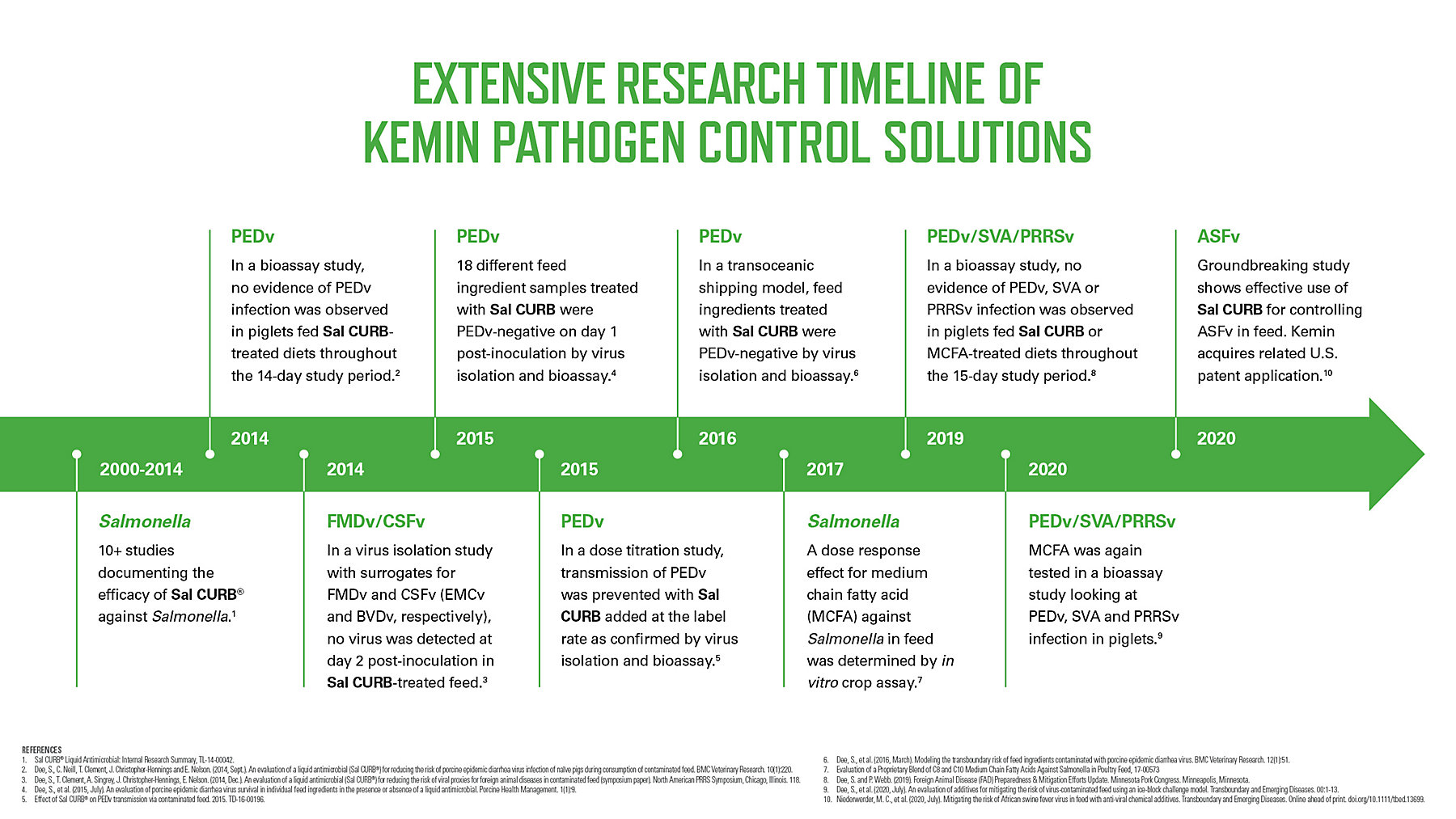

“Over the last eight years, the body of evidence has grown that shows feed needs to be a part of the comprehensive plan of biosecurity,” Dee said.

Biosecurity spotlight: feed

In early 2014, PEDv appeared and spread rapidly throughout the U.S. herd. Initially, affected farms were geographically diverse, and no obvious connections tied them together. That’s when some in the industry began to investigate the role of feed as a vector for the virus. Dee and his team at Pipestone conducted studies which confirmed the presence of the virus in feed bins and demonstrated that pigs who ate feed from these bins became infected. This led to the first ground-breaking study that showed that PEDv could be transmitted through feed.

“No one had ever considered feed as a vehicle for virus pathogens to move. Maybe Salmonella, maybe mycotoxins, but not viruses,” Dee said.

A few years later, Dee led another study that explored the survivability of pathogens in feed and feed ingredients during a transoceanic journey. This study was inspired when one of Dee’s Pipestone colleagues noticed bags of feed imported from China on a farm and wondered if viruses could survive the trip from China to the U.S. Dee and his team simulated a 37-day journey from China to Des Moines, Iowa based on an actual transport route, as well as another trip from eastern Europe to Des Moines, Iowa. Regardless of the simulated journey route, it was found that many pathogens could survive and remain infective in various ingredient matrices, ASFv included.

The “Ice Block Challenge” and pathogen mitigation

After confirming that viruses can indeed spread through feed, Dee worked with Kemin and others in the industry to further research regarding the efficacy of feed additives with potential feed biosecurity benefits.

Dee led a study that invited feed additive companies in the U.S. to participate in an “ice block challenge,” which attempted to recreate real-world conditions in which viruses might spread through feed. This natural feeding model is novel and important — as pigs have repeated exposure to feed, and therefore pathogens in feed, that increase the risk of infection. The researchers froze concentrations of PEDv, PRRSv and Seneca A (SVA) virus (a surrogate for FMDv) into one-pound blocks of ice, each of which was dropped into a bin of feed that fed 96 pigs (overall, 2,880 weaned pigs were involved in the study). Some of the feed bins had been treated with one of 15 different mitigants, while the others had not been treated (control). The study compared the mitigated feed to the non-mitigated feed, measuring variables such as infection rate (PCR), clinical signs, mortality and average daily gain in the pigs. All but one of the mitigants showed some efficacy at preventing infection, depending on the virus tested.

One thing was clear through the study, treating feed with a mitigant will drastically lower risk. But with biosecurity goals in mind, producers need to be clear in whether they are pursuing a mitigation effect or a high efficacy, disinfection effect.

Sal CURB® from Kemin has not only been proven to maintain the Salmonella-negative status of feed and feed ingredients, but the “Ice Block Challenge” further tested its efficacy across multiple viruses.

“To me, the gold standard of mitigants is Sal CURB, because that is what we started with, and it continues to show itself against ASFv and other viruses to be the best,” Dee said.