Though pigs (usually three weeks of age or older) are the only ones that become symptomatic from the disease, rats, mice, dogs, birds and flies – all common denizens of today’s large hog farms – are also potential hosts of the pathogen that causes the disease. It can also survive for up to 18 days in the soil or 60 days in a water supply. Infected sows may not become symptomatic, but can transmit the pathogen – and resulting symptoms – to piglets. Altogether, the ease of transmission and multiple host possibilities on a farm make swine dysentery difficult to control, especially in larger animals, like on a finisher farm.

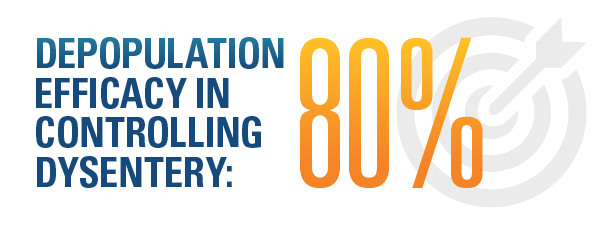

“Any organic material will cause proliferation. On top of animal-to-animal contact as a cause, it will stay in any organic material on the farm – fecal matter and dirt on the floor and left under the slats will have the disease on it, it will be in the lagoon and in the rodents around the farm,” de Souza said. “Once you have the disease, it can be difficult to get rid of. As soon as you can get rid of it and get the farm cleaned up, you are fine. But it can come in again with any infected animal.”

Managing Swine Dysentery

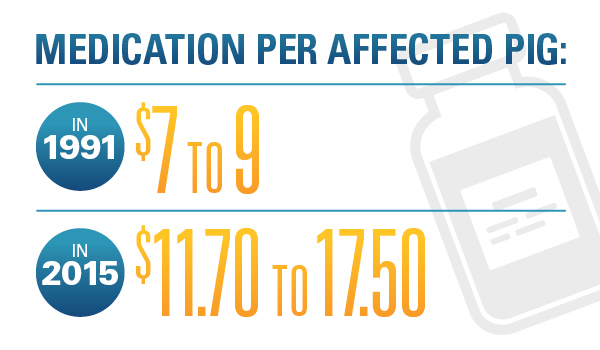

Early swine dysentery treatment options were largely comprised of organic arsenicals and later, antibiotics. Though much more effective in controlling the disease, the latter is not the viable option it once was because of antibiotic withdrawal timeframes due to concerns about resistance and overall animal and consumer health.

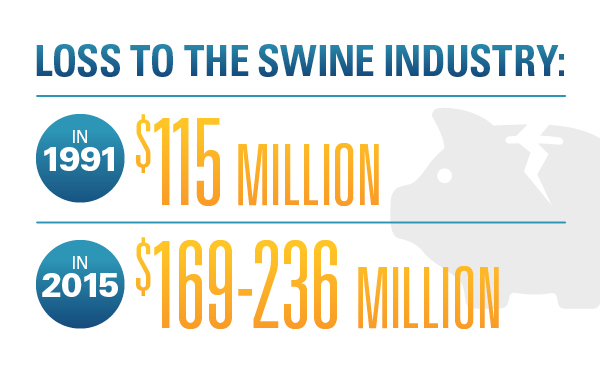

Treating swine dysentery has considerable implications for producers, be it in the cost, distribution and management of antibiotic treatments or herd logistics management required to prevent the proliferation of swine dysentery. Though de Souza said antibiotics like Denagard® – a common feed additive – have a smaller price tag than the cost to take more comprehensive management measures, using such a treatment has implications of its own, chief among them is the growing scrutiny of such products’ use in livestock animals like pigs.