Mycotoxins are a perennial challenge for livestock and poultry production systems given their often-undetected presence in a vast majority of feeds. Recent data indicate that around 90% of feed grain samples tested show some mycotoxin contamination, while at least 1 of the 5 most prevalent mycotoxins — T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON), fumonisin, zearalenone and aflatoxin — was present in 75% of samples. More importantly, more than half of samples contained multiple mycotoxins. To date, the interaction of mycotoxins has not been an active research area because of the vastness and expense associated with the research needs. The additive, synergistic and antagonistic interactions of mycotoxins — while still being researched — can certainly multiply overall adverse health effects, leading to costly production losses. Worse yet, even at low levels, and alone or in combination, consumption of mycotoxin-contaminated feeds has the potential to cause intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress, thereby decreasing animal health and production.

The good news? This doesn't mean you cannot be prepared in advance to limit the acute and chronic damage mycotoxins can cause when your herd or flock consumes contaminated feed. A holistic approach to managing the challenge can help maintain animal health and productivity even in the face of multiple potentially damaging mycotoxins.

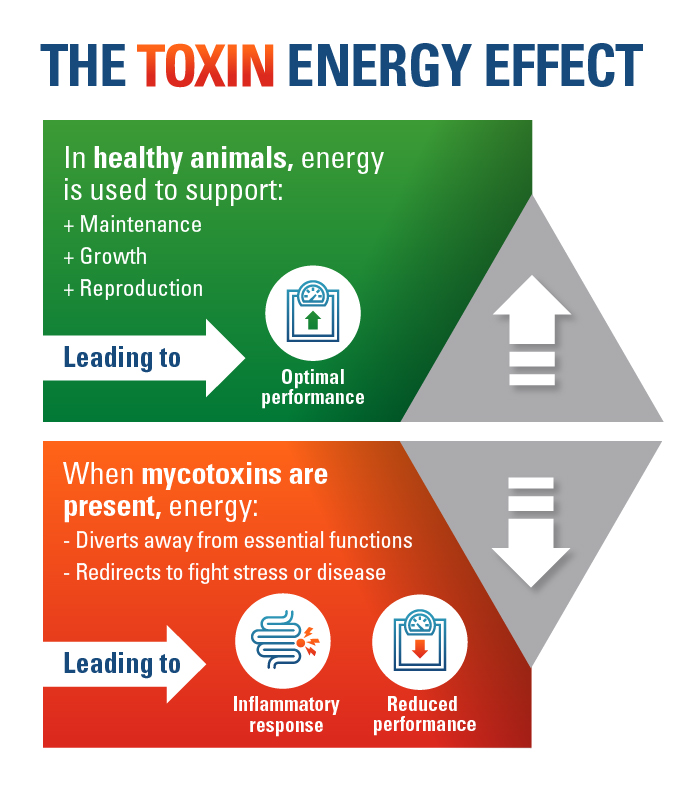

Molds present in feed grains produce mycotoxins as a response to environmental stress. When an animal consumes contaminated grain, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the first target of harmful mycotoxins. Exposure of the intestinal barrier to mycotoxins can cause inflammation — and later oxidative stress — which, if it results in breach of the epithelial barrier, can lead to systemic harmful effects. For animals experiencing leaky gut, or the breaking down of epithelial tight junctions typically caused by stress, the risk of systemic harmful mycotoxin effects significantly increases.